The Quiet Erasure: Black History Stories Being Removed From U.S. Classrooms Right Now

Share

Across the United States, Black history, once a critical part of school curricula, is being quietly narrowed or removed altogether, leaving students with a stripped-down version of the nation’s story. From textbooks to lesson plans to classroom discussions about slavery, civil rights, and the ongoing impact of systemic racism, educators and civil rights advocates are raising alarms that a major chapter of American history is being sidelined at a time when it matters most.

This shift is not always sudden or headline-grabbing. In many districts, changes are happening quietly, through revised standards, textbook adoptions, or administrative directives that limit how deeply educators can engage with topics related to race, racial injustice, and the lived experiences of Black Americans. What critics call “curriculum narrowing” can look like the removal of books by Black authors, fewer class discussions on figures like Martin Luther King Jr. or Ella Baker, or assignments that avoid topics like the Tulsa Race Massacre or the civil rights movement.

The debate is rooted in ongoing conflicts over how U.S. history should be taught. Some policymakers and parent groups argue that lessons about race and systemic inequality are “divisive,” “one-sided,” or inappropriate for certain grade levels. This argument has, in turn, led to legislation in several states that limits how teachers can address topics related to race, power, and identity. In practice, these laws can discourage or prohibit educators from fully exploring the history of slavery, Jim Crow, mass incarceration, and resistance movements led by Black Americans.

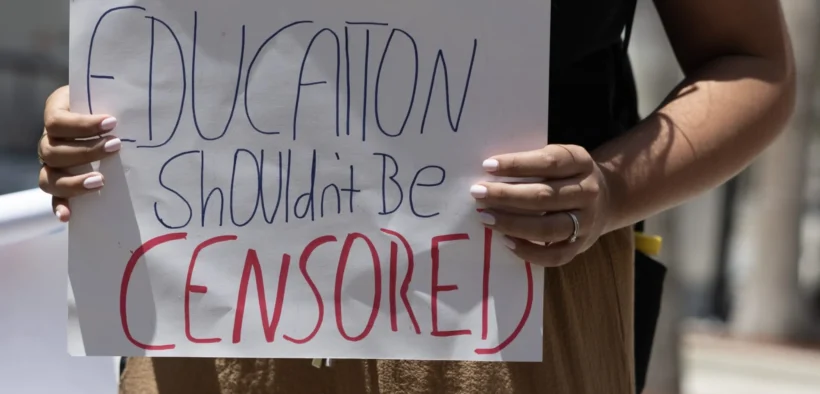

Supporters of these restrictions say they aim to promote “patriotic education” and ensure that students focus on uplifting themes rather than complex and painful realities. Critics charge that this is a form of censorship that erases vital context from the history that shapes contemporary society, leaving students less equipped to understand structural inequality and their roles within it.

The effects are already visible in classrooms. Teachers report receiving guidance to avoid content deemed controversial or politically sensitive. Textbook publishers, responding to shifting state standards, often reduce chapters on the trans-Atlantic slave trade, Reconstruction, Black Power, and racial justice movements to avoid rejection in large markets. In some districts, resources about local Black history have been removed from reading lists without explanation.

For Black students, the impact is personal. Black history isn’t an abstraction, it is lived experience, family memory, and cultural heritage. Stories of resistance, brilliance, and community resilience connect students to their roots and reinforce identity in a society that too often marginalizes Black contributions.

Experts warn that removing or diluting Black history from classrooms doesn’t make the past less real; it simply makes future generations less prepared to confront the legacy of injustice that still shapes American life. Without understanding the full arc of U.S. history, including its chapters of atrocity and activism, students risk leaving school with an incomplete and sanitized view of the world.

Civil rights scholars point out that history has always been contested terrain. What is included, excluded, or emphasized in textbooks and classrooms reflects power, politics, and priorities. The current debates are not new, but the momentum behind them has grown as state governments expand control over educational standards and as cultural fights over identity, history, and national narrative intensify.

Parents, teachers, and community leaders who oppose the narrowing of Black history are organizing responses. They seek to protect inclusive curricula through school board elections, curriculum review committees, and legal challenges. In some districts, educators and advocates are creating supplementary materials, after-school programs, and community history projects to ensure young people still access the stories that official textbooks may marginalize.

The stakes are high. How students learn about slavery, segregation, civil rights, and the contributions of Black Americans influences how they think about citizenship, justice, and each other. When the lessons are incomplete, the consequences are not merely academic, they shape empathy, civic engagement, and collective memory.

At a moment when racial inequity remains a defining challenge in the United States, the movement to remove or narrow Black history from classrooms is more than a curriculum fight. It is a battle over who belongs in the story of America, who gets counted as a contributor to the nation’s progress, and how future generations will understand the meaning of justice, freedom, and equality in their own lives.