“This Is a Lie”: Nigerians Push Back on New York Times Story Accused of Inciting Hatred Against Igbos

Share

“This is a lie.”

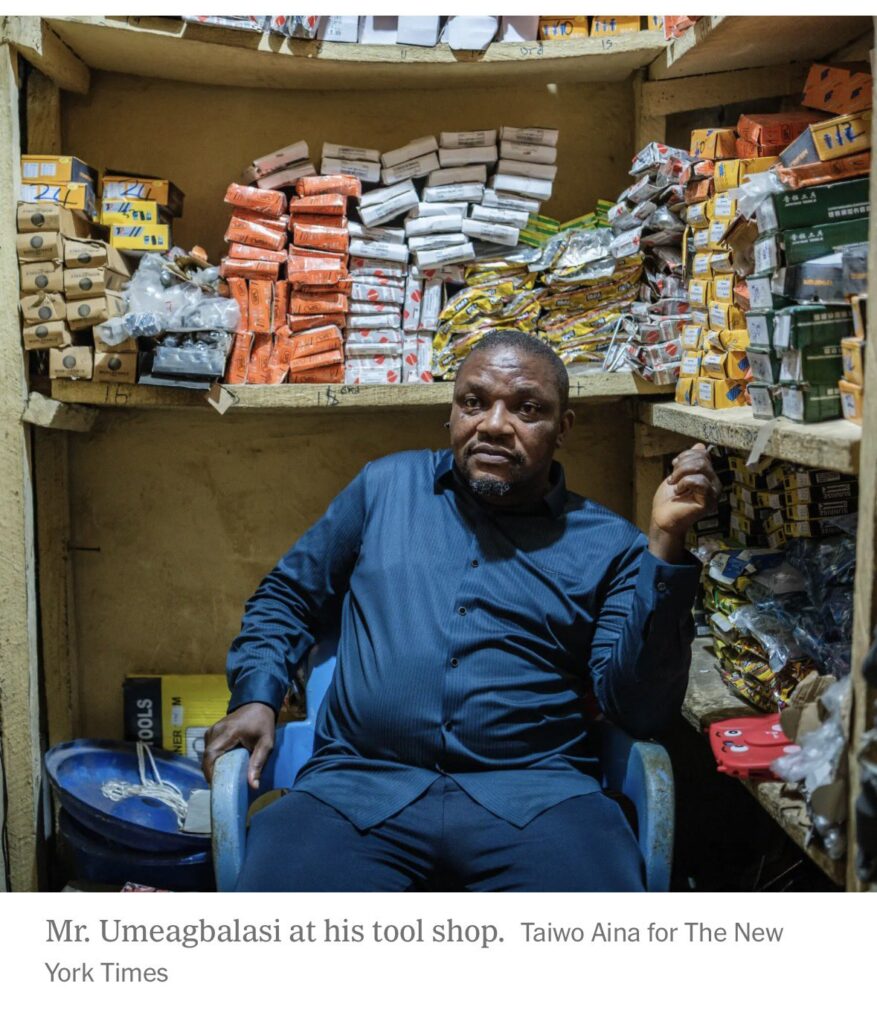

Those are the words many Nigerians, particularly within the Igbo community, are using to describe a recent New York Times report that claimed a small-market trader in Onitsha helped influence U.S. military action in Nigeria. To critics, the story is not just inaccurate, it is dangerous. They argue that the framing risks turning public anger toward an already vulnerable ethnic group while obscuring the deeper reality of terrorism, state failure, and political maneuvering in Nigeria.

The controversy follows U.S. strikes in northern Nigeria that were initially described by Nigerian officials as coordinated efforts between Washington and Abuja to target terrorist hideouts. At the time, the government emphasized partnership and consent. But as backlash grew in the north, where extremist groups like Boko Haram, ISWAP, and bandit networks have long operated, the narrative began to shift.

Instead of maintaining that the operation was a joint security effort, critics say a new storyline emerged: that an ordinary Igbo trader had somehow influenced the President of the United States to strike Nigeria. To many observers, the claim is implausible on its face. How could a screwdriver seller in a local market wield the kind of access or influence required to move U.S. military policy?

For Igbos, the implications are far more serious than bad journalism. The community has long existed under the shadow of historic hostility dating back to the Biafran War. In many parts of Nigeria, Igbos are viewed with suspicion, and they have frequently been blamed for political or economic grievances unrelated to them. Critics argue that positioning an Igbo civilian as the catalyst for foreign military action feeds a familiar and dangerous pattern, using the Igbo people as a convenient enemy.

In a country where ethnic tension can quickly become lethal, narratives matter. Terrorist groups and extremist sympathizers often exploit media framing to justify retaliation. Community leaders warn that suggesting an Igbo individual “invited” U.S. strikes could be read by militants as permission to target Igbo communities, most of whom are Christian and already face insecurity across northern regions.

The backlash also highlights a deeper grievance: while terrorist violence has devastated Christian communities for years, many Nigerians believe international attention has been muted. Kidnappings, village massacres, and church attacks continue, often with little accountability. Critics argue that rather than confronting these failures, political elites benefit from redirecting scrutiny, away from the state’s inability to protect citizens and toward a scapegoated group.

For those pushing back, the issue is not only about one article. It is about how global media can unintentionally, or carelessly, reshape internal conflicts in fragile societies. When international outlets amplify unverified or politically convenient narratives, they can legitimize local propaganda and embolden those who already trade in division.

The Igbo response is rooted in survival. Many remember how rhetoric preceded violence in the past. They see echoes of that history in a story that transforms a complex security crisis into a tale of ethnic blame. What they are asking for is not silence, but responsibility, reporting that interrogates power rather than redirecting danger toward the powerless.

In moments like this, journalism does more than inform. It signals who is believed, who is protected, and who can be sacrificed in the public imagination. For Nigerians speaking out, the demand is simple: do not tell a story that can cost lives.