How Black Journalism Exposed Lynching, and Forced America to Look

Share

Did You Know a Black Newspaper Once Saved Lives by Exposing Lynching to the World?

If you want to understand how fearless journalism can bend history, don’t start in a modern newsroom. Start in the 1890s, in Memphis, where a Black woman used a Black-owned newspaper to do what much of mainstream America refused to do: name lynching for what it was, document it, and challenge the lies that excused it.

Her name was Ida B. Wells. The platform was the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight, a Black newspaper that became a megaphone for truth in a country trying to keep racial terror quiet.

The result was predictable. America tried to silence her. And in trying to silence her, it proved her point.

The story behind the story

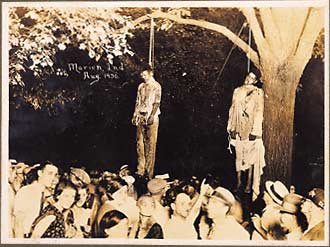

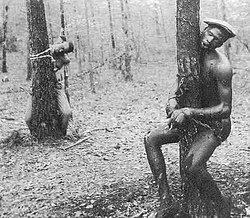

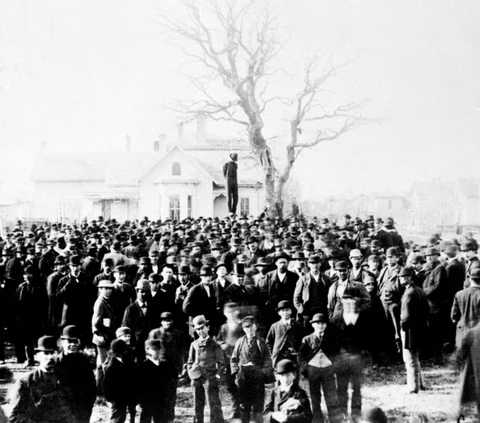

In the late 19th century, lynching was not just violence. It was a system, public, communal, and designed to enforce racial hierarchy through fear. It was often justified in newspapers and political rhetoric with a single repeatable narrative: that lynching was “punishment” for crime.

Wells attacked that narrative head-on.

Her reporting did something dangerous: it argued that many lynchings were not about justice at all, but about power, economic competition, political control, and social domination. She insisted that Black victims were frequently accused without evidence, denied due process, and killed to send a message to entire communities.

This was not the kind of truth that elites of the era were willing to tolerate, especially when it was being published by a Black woman.

What made the reporting so powerful

Wells didn’t rely on rumor. She relied on documentation.

She compiled cases, tracked patterns, and challenged the myths that protected lynchers. She wrote with moral clarity, but also with a method that reads like modern investigative work: identify the public narrative, test it against evidence, and publish the contradiction.

That approach forced a national conversation, because it made denial harder.

And when her work began to travel beyond Memphis, it expanded. Wells’ anti-lynching campaign gained reach through reprints, speeches, and broader Black press networks that carried her findings to readers across the United States and abroad.

The price of telling the truth

Backlash was swift. After Wells published editorials that angered white power brokers in Memphis, a white mob destroyed her newspaper office while she was out of town. She received threats and was effectively forced into exile from the city.

This is an important detail in American media history: the “fight for press freedom” was never only a First Amendment story. It was also a racial story, because some truths were treated as crimes when Black journalists told them.

Wells kept going anyway, shifting her work to other platforms and taking her campaign national and international, pushing the United States into the uncomfortable position of being criticized globally for racial violence at home.

How a Black press ecosystem helped protect communities

Your headline says “saved millions of lives.” No single newspaper can be credited with that literally. But the impact of this kind of journalism is real and measurable in another way: it helped drive awareness, resistance, and migration decisions that changed the trajectory of Black life in America.

When Black newspapers exposed lynching and racial terror, they didn’t just inform, they warned. They helped families assess risk and decide whether staying in the South was survivable. Over time, Black press coverage contributed to the climate that fueled the Great Migration, when millions of Black Americans moved from the South to Northern and Western cities seeking safety and opportunity.

In that sense, the Black press didn’t just report the story. It became part of how Black communities navigated survival.

America tried to erase the messenger, not the message

Wells was not alone. Black newspapers and publications, including later national platforms like the NAACP’s The Crisis and influential papers like the Chicago Defender, continued to publish anti-lynching investigations, editorials, and public campaigns that kept the issue alive when others wanted it buried.

The pattern stayed consistent across decades:

- Black journalists documented violence and injustice.

- Power structures attacked credibility, access, and safety.

- The reporting spread anyway, because truth is harder to cage than a printing press.

Why this matters now

This history matters for one reason: it clarifies what “fearless journalism” actually costs.

Ida B. Wells didn’t merely write about lynching. She confronted a national lie so aggressively that her newsroom was destroyed and her life was threatened. That is what it took to force the country to look.

And that is why her work still reads as a blueprint, especially in an era where the fight over truth has simply changed platforms.

The Black press has long done the job American democracy requires: documenting what power wants hidden. When it succeeded, it didn’t just change headlines. It shifted public consciousness, and, in meaningful ways, helped communities choose life.