The Black Surgeon Behind an Early Heart Surgery Breakthrough

Share

Did You Know the First Open-Heart Surgery Was Performed by a Black Surgeon No One Talks About?

It’s a headline built to stop a scroll, and it points to a real story that deserves attention. But the history is slightly more complicated than the claim suggests.

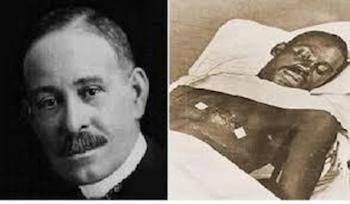

A Black surgeon, Dr. Daniel Hale Williams, performed a landmark heart operation in 1893 in Chicago, an extraordinary achievement for the era, especially given the lack of antibiotics, modern imaging, and today’s surgical technology. The patient survived. In many tellings, it’s described as an early “open-heart” surgery.

What’s often left out is the nuance: Williams did not perform “open-heart surgery” as it’s defined today (which typically involves opening the chest and operating on the heart, often with a heart-lung bypass machine). Instead, he performed a daring operation to repair a wound to the pericardium, the sac surrounding the heart, after a stabbing. It was still a major breakthrough, and it remains one of the most important early chapters in cardiac surgery.

The night that made medical history

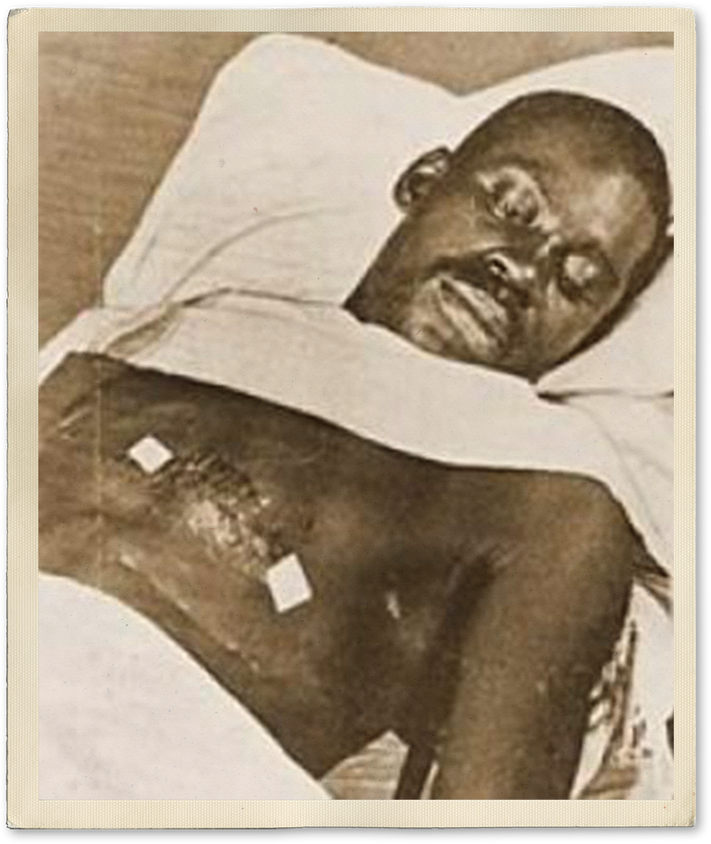

In the summer of 1893, a young man named James Cornish was brought to Chicago’s Provident Hospital with a stab wound near the heart. At the time, heart injuries were widely considered a death sentence. Surgeons rarely attempted intervention because infection and uncontrolled bleeding were common, and fatal.

Williams operated anyway.

He opened Cornish’s chest, located the wound, and repaired damage in the area around the heart. Cornish survived the immediate crisis and, according to historical accounts, lived for years afterward. In an era where even basic surgical sanitation was still evolving, that outcome was remarkable.

Why it mattered beyond the operating table

Williams’ achievement wasn’t only clinical, it was institutional.

He helped found Provident Hospital, widely recognized as one of the first Black-owned and -operated hospitals in the United States, created at a time when Black physicians and patients were frequently excluded from mainstream medical institutions. Provident became a training ground and a lifeline, proving that Black medical excellence could thrive even under rigid segregation.

That’s part of why Williams’ story carries such weight: it sits at the intersection of innovation and access, skill and system.

The “first open-heart surgery” claim, and what’s accurate

If someone says, “the first open-heart surgery was done by a Black surgeon,” they are usually referring to Williams’ 1893 operation because it involved opening the chest and operating in the region of the heart with a successful outcome.

But if we’re being medically precise, the first successful open-heart procedure using a heart-lung machine is typically credited to surgeon John H. Gibbon Jr. in 1953, a milestone that made many complex heart repairs possible on a stopped, bloodless field.

So the truth is this:

- Williams performed one of the earliest successful surgeries involving the heart region, a historic feat.

- Modern open-heart surgery (with bypass) came decades later, building on earlier pioneers like Williams.

The corrected version of the headline still hits hard, and remains historically important:

A Black surgeon performed one of the earliest successful heart operations in 1893, and his role is still not widely taught.

Why so few people know his name

Williams’ story sits in a familiar American pattern: contributions by Black innovators get condensed, disputed, or excluded, especially when those contributions disrupt the “standard” narrative of who built modern institutions.

Medical history, like political history, often becomes a story of the best-funded institutions and the names they promoted. Williams worked against the grain, building care systems for Black communities while doing elite-level surgery in a period that barely recognized Black professionals as equals.

That combination, excellence plus institution-building, should have made him a household name.

The real takeaway

If your goal is to spark readership with truth, this story is powerful when told accurately:

Dr. Daniel Hale Williams didn’t just perform a groundbreaking heart operation in 1893. He did it while building a hospital ecosystem that expanded Black access to care and professional training. His legacy is not only about a single surgery, it’s about what it took to make that surgery possible in the first place.