Ella Baker: The Grassroots Architect of the Civil Rights Movement Born and Laid to Rest on December 13

Share

Ella Baker remains one of the most influential yet understated figures in American civil rights history. Born on December 13, 1903, and passing away on December 13, 1986, Baker’s life came full circle on the same date, marking a legacy defined not by speeches or spotlight, but by strategy, organizing, and people-powered leadership that reshaped the movement from the ground up.

Born in Norfolk, Virginia, and raised in North Carolina, Baker grew up listening to her grandmother’s stories of resistance to slavery, stories that instilled in her a deep belief in collective action and self-determination. After graduating as valedictorian from Shaw University, Baker moved to New York City during the Harlem Renaissance, where she became involved in labor organizing and community activism during the Great Depression.

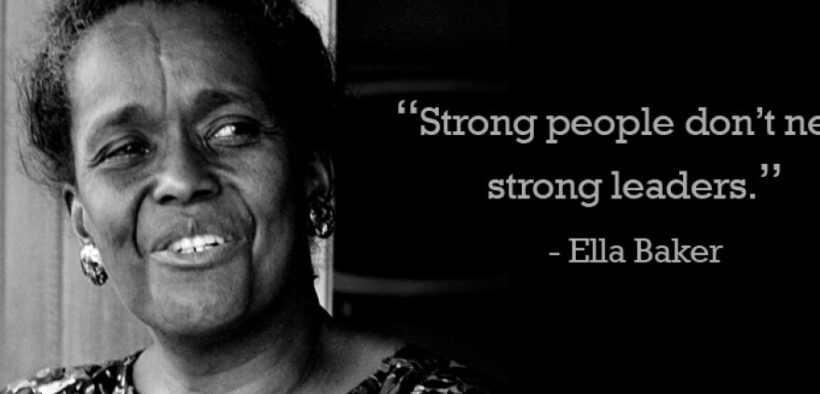

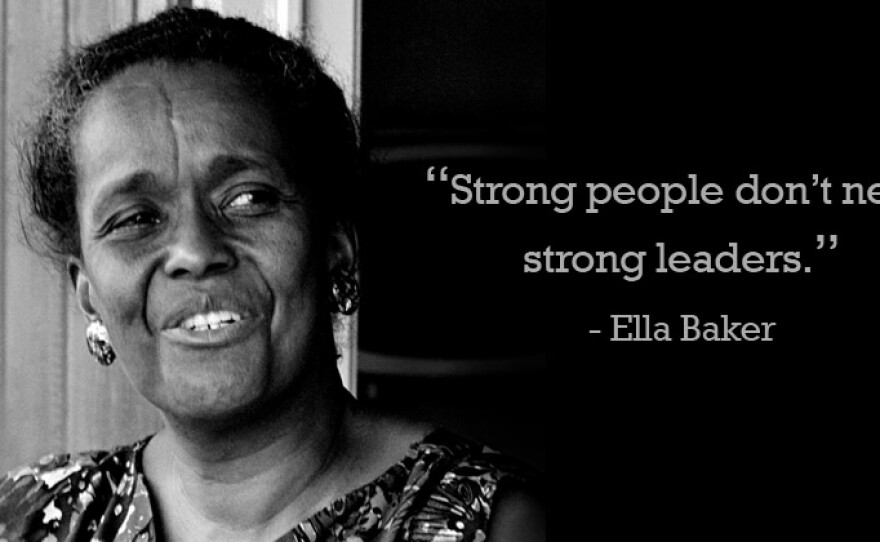

Baker’s most enduring contribution to the Civil Rights Movement was her philosophy of participatory democracy. She rejected the idea that movements should revolve around charismatic male leaders, arguing instead that real power comes from ordinary people organizing themselves. “Strong people don’t need strong leaders,” she famously believed, a principle that placed her at odds with the era’s more hierarchical leadership structures.

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, Baker worked closely with the NAACP, serving as a field secretary and later director of branches. She traveled extensively across the South, building local chapters and empowering everyday Black citizens to challenge segregation and voter suppression. Her work helped lay the foundation for the legal and grassroots victories that followed.

In 1957, Baker became a key organizer behind the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), though she grew increasingly frustrated with its top-down leadership style. Her greatest impact came in 1960, when she helped convene young activists following the Greensboro sit-ins. That meeting led to the formation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), one of the most radical and effective civil rights organizations of the era.

Through SNCC, Baker mentored a generation of leaders, including Diane Nash, Bob Moses, and John Lewis, encouraging them to trust their own leadership and organize directly with local communities. SNCC’s voter registration drives and grassroots campaigns fundamentally altered the movement’s direction and intensity.

Despite her enormous influence, Baker rarely sought public recognition. She avoided the spotlight, refused honorary titles, and consistently redirected attention toward the collective work of communities. This deliberate humility contributed to her relative absence from mainstream civil rights narratives, even as her strategies shaped nearly every major campaign of the 1960s.

Ella Baker died on December 13, 1986, exactly 83 years after she was born. Her death marked the loss of a quiet revolutionary whose fingerprints are found across the modern struggle for justice, from voting rights movements to contemporary organizing models that prioritize local leadership and accountability.

Today, Ella Baker’s legacy endures wherever movements are built from the bottom up. Her life serves as a reminder that lasting change is not driven by individual fame, but by organized people who understand their own power.